Picture this: it’s an hour before checkout in a Kyoto hotel. A kilted Scotsman approaches the reception desk, hoarse and probably still a little bit drunk. He croaks an almost silent “Sumimasen” to a bemused concierge. We’d been in Japan three days, and we’d already been on stage for ten of the last forty-eight hours. I could speak very little Japanese, and that morning, I could speak very little of anything.

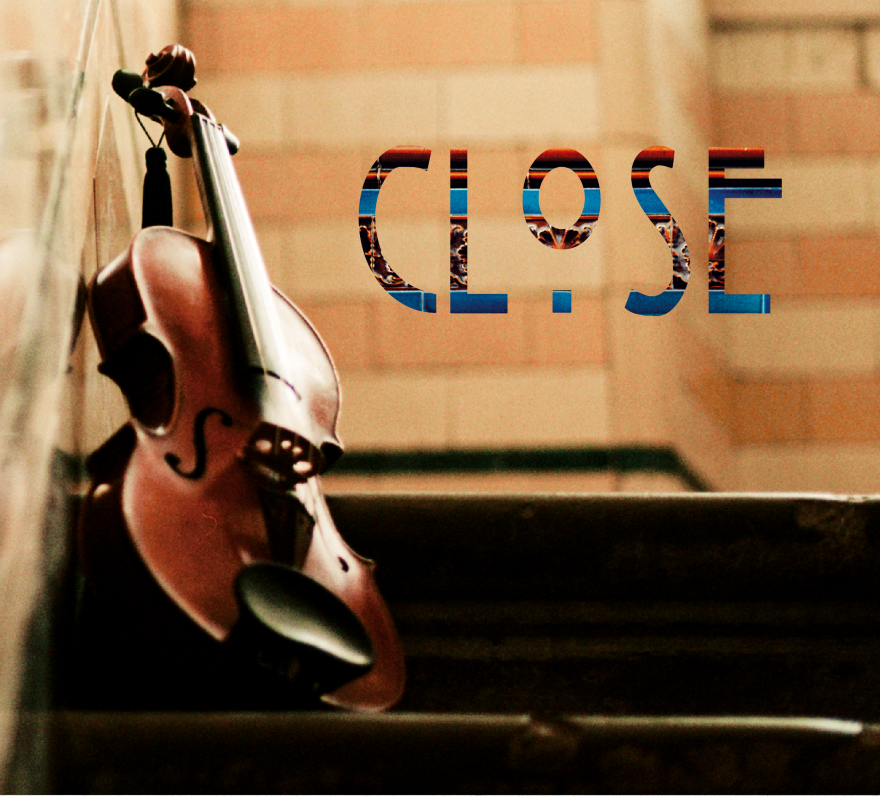

I’m Davie, and I’m the singer for Bruach. We’re a Scottish folk rock band, some would say Celtic punk. I’ve been known as the wee bouncy dude with the Duracell batteries for years, but now I’ve found myself in a band of people who carry the same energy. We bring it to every show, with Kayo Ono’s fiddle tearing through reels, Sean Wilkie’s bass thumping like a heartbeat, Niall Crookston’s drums kicking like a mule, and Kris Pheely’s guitar tying it all together. We love The Corries and Gaberlunzie, but our sound is closer to Scotia or Peat and Diesel. We live for getting the crowd going; clapping, singing, dancing along, or sometimes just shouting whatever nonsense we throw at them.

So how did we end up staggering around a hotel in Kyoto? It all started with a daft moment at Hootananny in Inverness last August. We were mid-set, calling for a bit of crowd interaction. All For Me Sauce is our take on All For Me Grog. It’s a family-friendly version with a dafter edge. Instead of “tobacco,” the crowd shouts “tomato.” There’s a story behind it, but we won’t get into it here. This American guy refused to play along. We had some banter and called him “Tobacco guy.” Afterwards, he was chatting to Kayo – in Japanese! He told her that he lived in Kyoto now, and suggested the Osaka Expo.

We all laughed our kilts off. Japan? The furthest we’d been so far was Skye! But Kayo grabbed the idea like a lifeline. “My ties to Japan faded after twenty years in the UK,” she told us later. “This was my chance to show you my home.” She applied, fully expecting nothing, and we didn’t hear for months. Then, just before Christmas, bam! We’d been selected to host a stage at the Expo. Who knew a pub chat could send us round the world?

It sounds simple when you say it quickly. “We’re off to Japan!” Easy, right? But getting five musicians to Japan with instruments, kilts, and enough energy to host a full-day stage is no small feat. This wasn’t just a half-hour set. It was Scottish food tasting, ceilidh dancing, and a Celtic instrument experience, and all that on top of our music. That kind of show doesn’t fall together by accident.

The truth is, Kayo did most of the heavy lifting. Flights, accommodation, schedules, venues, translations, endless emails, sleepless nights, the lot. The rest of us pitched in the only way we knew how: gigging harder than ever. Coach and Horses in Dumfries, Waxy’s in Glasgow, McKays in Pitlochry, The Havelock in Nairn, among others. We booked everywhere and anywhere that would have us. Every pint poured, every t-shirt sold, every raffle ticket was another step closer to Osaka. We’re not normally about the money, but we needed it now.

And somewhere in the middle of that grind, Japanese influences started to creep in. Kayo, our honorary Scot (Sean would say “She’s no honorary, she’s just Scottish!”), started wearing a kimono at practice, and on stage, her traditional dress against our kilts. It showed our intent. Japan was going to be a part of our music.

We began with Highland Soldier, a tune Kayo had written back in Japan, paired with a 19th-century Scottish broadsheet ballad. Those old ballads were meant to be shared. Their words could be sung to all sorts of melodies. Putting it to Kayo’s tune felt like a bridge between her two homes.

Then came Sakura Air An Duine Sith, a mash-up of the Japanese folk song Sakura Sakura with The Atholl Highlanders. The title itself was a blend, half Japanese, half Gaelic, and the verses mixed Japanese, English, and, increasingly, modern Scots. We learned Train Train, the Japanese punk anthem of the 90s, and translated it into Scots (or maybe just Glaswegian). Later in Japan, we met Tetsuya Kajiwara, the drummer of The Blue Hearts, who wrote the original. If we get his blessing, our version might yet see daylight.

July came around so quickly, I swear we skipped a month. Did we have May? It was really happening! Landing in Tokyo was like stepping into a video game. All neon, noise, vending machines selling cold coffee. Those soon became my morning ritual. The hotel omelette was so fluffy I could’ve napped on it. Then the bullet train to Osaka, where I promptly got stuck behind the ticket gates like a numpty and missed the meeting point. Nobody slept that first night. The Expo stage was waiting the next day.

It was 35 degrees, and humid enough to melt. As Pheely put it, “the scale of the thing is incredible.” He was right, but we didn’t have time to look around. We had a stage to set up. I was cream crackered before we even opened the doors. I don’t know how Kayo did it, she was the only one of us who could communicate with most people, so she was everywhere, like a blur. Seconds later (or so it seemed), I was calling ceilidh dances while she translated and demonstrated at the same time. Just like home, we had volunteers tripping over Gay Gordons and laughing their heads off. The Dashing White Sergeant had them grinning ear to ear. They got it in the end, proving that Scottish country dancing can travel.

That’s when we met Shima. He turned up to Expo in a kilt with a Bonnie Scotland flag draped over his shoulders. He danced, he tried the toy bagpipes, he played with the accordion. Seeing a Japanese fan in a kilt reminded us that our cultures had already been in conversation long before we turned up.

Then came our main set. We had Scots and Japanese lyrics side by side on a massive 10-metre screen behind us. People sang along to Scottish songs in Scots, then told us afterwards that the translations gave them a new understanding of lyrics they’d known for years. We’d been worried about the crowd participation bits we had in the set, but we needn’t have worried, they sang along to Wild Mountain Thyme and shouted “tomato!” just like back home, and the songs we added for them, like Train Train, went down a storm! They even called for an encore! What else, but our first single, Big Strong Belle, to finish off the night? It was a special moment, one I won’t forget. Sean roared, “We love you, Osaka!” and we all meant it!

Hooking up with Japanese musicians was the heart of it. Souichirio and Yogakai, masters of Gagaku, Japan’s ancient court music, were absolute legends. They were running our Celtic musical instrument experience and our merch stand as well as playing the support slots. Joining them for Kimi Ga Yo, the Japanese national anthem, was magic. Kayo’s fiddle wove with their flutes, and I sang the vocal in my best Japanese. I don’t think I butchered it.

We recorded the Expo set live. When I listen back, I can hear the sheer relief and joy in it. That mix of “we made it” and “let’s give them everything we’ve got,” it’s plain to hear. That show pulled us closer together as a band. The road and the miles from Dundee and the work had been worth it.

Yogakai later took us for a Gagaku lesson, where they had us puffing on the Hichiriki, a bamboo double-reed flute which tickled my lips like a bee’s wing. The Ryuteki or Dragon flute, the hero’s instrument, was Sean’s favourite. He bought one, though his fiancée’s not thrilled about the noise. “Gagaku was brilliant! Love trying new gear!” he said. They let us wear traditional kimonos. I chose yellow because, aye, I’m a showoff. We banged Tsuri-daiko drums, their ceremonial beat feeling like the slow build in our reels but way more polished. Niall called it “the most Japanese thing we did.” It’s got us itching to mix those haunting melodies into our next tracks.

The gigs after Expo had their own flavour. At Stones in Kyoto, the crowd spilled into the street! Scots, Kiwis, Belgians, Americans mixing with locals, clapping and singing and shouting “I Love You!”. That’s Bruach, though. We get folk dancing, from Osaka to Oban. At one point, I was handed a “mega pint” of Guinness on stage. I tried to split the G, only to find it was in a Stella glass. Sacrilege! By the end of the night, there wasn’t a drop of Guinness left in the bar. We met a Scottish couple there, too, and it turned out I knew the guy’s uncle. Half a world away and still bumping into neighbours.

Tin’s Hall in Osaka was so cool. Goro from The Goro Band mirrored my every move like he’d been touring with us for years. Their ’50s rock ’n’ roll shapes were a show in themselves. We’re going to do a bit more of that. Meg had been our contact in The Goro Band, and when we realised that Sean wouldn’t be there for the duration, she sorted out bassists for the remaining dates. Then came the coup: Tetsuya Kajiwara from The Blue Hearts turned up. Not only that, he stayed for the whole show. Smashing out Train Train with him in the room was surreal. Kayo was starry-eyed for days.

The Enchant charity gig was another kind of special. Playing for neurodiverse kids hit home for me, as my son has ADHD/ASD. We ran ceilidh dances and the instrument experience with them. Some of them were right in there, but others needed a little encouragement. One kid saw a mosquito bite on my arm and made a buzzing sound, then said “Scratcha-scratcha!” No translation needed. Kayo thought I should join the dancing instead of calling it, but I’m a terrible dancer. Hopefully, my partner had fun, because he didn’t learn a step from me. Their smiles were everything. “Treasures I’ll carry,” Kayo said.

Japan is full of little bridges like that. Take Auld Lang Syne. They have a version of their own. Hotaru no Hikari is about time passing, which is in the same spirit as Burns. Some stations even play it for the last train of the night. When we played Auld Lang Syne at Expo, and the Japanese lyrics joined the Scots ones, it felt like a perfect circle. “During this trip,” said Kayo, “I made new friends, built new connections to Japan, and travelled with Bruach – my new family.”

Coming home, we didn’t want to lose that momentum. The Expo live recordings are being polished, with a bit more crowd sound mixed in. Highland Soldier will be the first release in early October. After that, we’re heading into the studio to record an EP including the Scots version of Train Train if we get permission. Maybe even some anime for fun, the Dan Da Dan theme is a banger.

We’re dreaming of a 2026 tour, but maybe we’ll just tour the West Coast of Scotland. If we do, the plan will be to reach some of the islands. We’re keeping the Japanese influence, Kayo has a Sho, and Sean’s Dragon flute. We want to incorporate them into some arrangements.

None of this would have happened without the people who backed us. So here’s the important bit: massive thanks to The Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation and Japan Society of Scotland. Thanks to Tommy the Tomato Guy, Souichiro and the Yogakai crew, Goro and Meg and The Goro Band, and everyone who bought a pint or a t-shirt along the way.

Japan is in our blood now. Somewhere between the kilts and the kimonos, between The Atholl Highlanders and Sakura Sakura, we found a shared language. If you come to a Bruach gig, we’ll be happy to teach you a few words of it. And if you shout “Tomato!”, we’ll know exactly where you’ve been.

Bruach

Website | Instagram | Facebook | Spotify

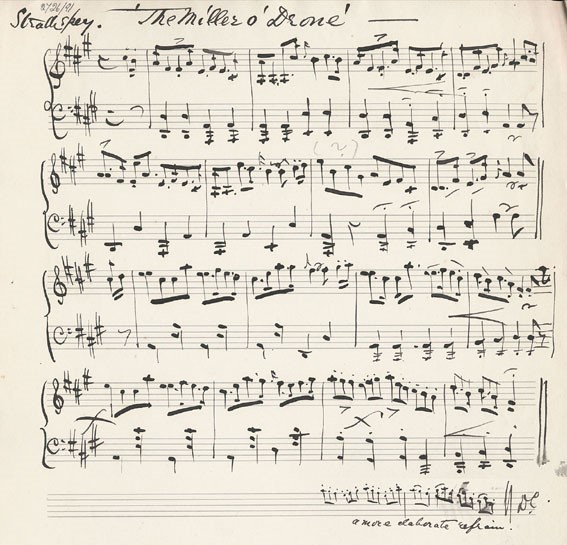

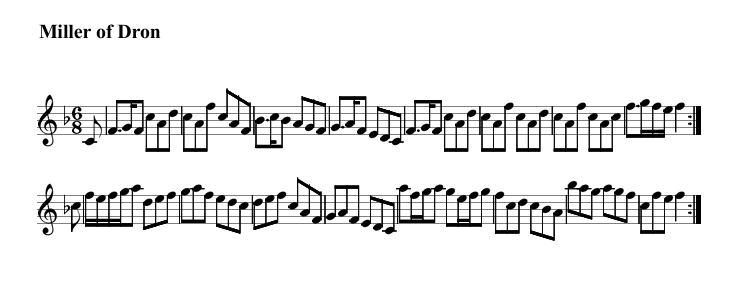

However, Stobie’s 1783 map doesn’t indicate that there was a mill there. The first Ordnance Survey map of 1867 shows by that time there was a mill. There are also no records that I could find showing the Perthshire Dron being spelled “Drone.” I began to get a hunch that this might not be the correct location and that I might have to look elsewhere.

However, Stobie’s 1783 map doesn’t indicate that there was a mill there. The first Ordnance Survey map of 1867 shows by that time there was a mill. There are also no records that I could find showing the Perthshire Dron being spelled “Drone.” I began to get a hunch that this might not be the correct location and that I might have to look elsewhere.

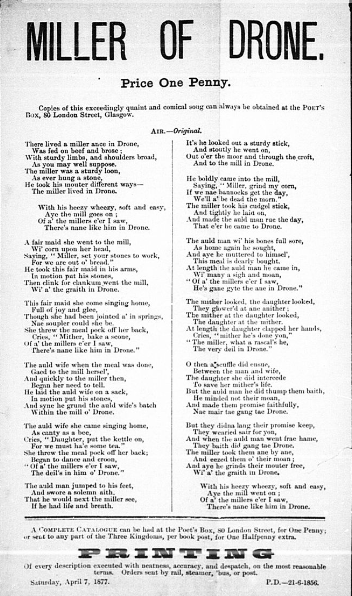

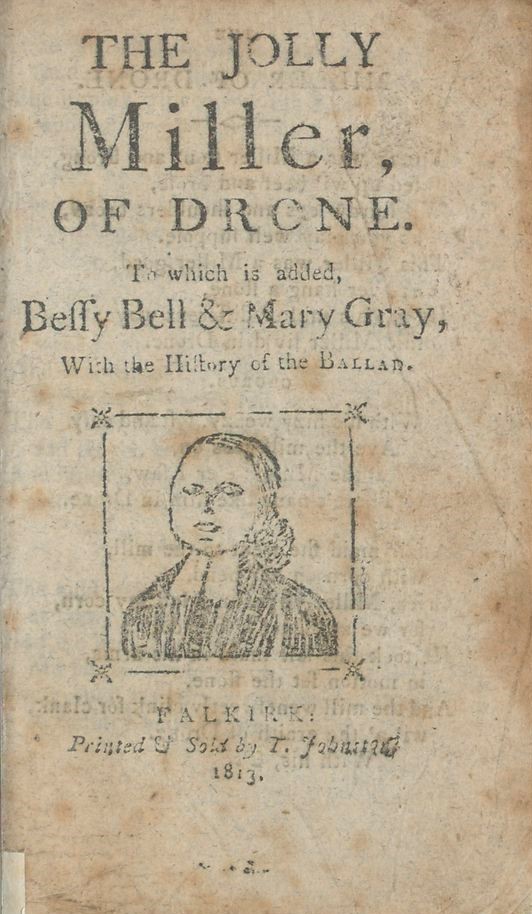

The next tunnel down the rabbit hole leads us to the bawdy C19th song, The Miller of Drone.

The next tunnel down the rabbit hole leads us to the bawdy C19th song, The Miller of Drone.

📷 Angus Murray singing at a public talk, Comunn Eachdraidh Nis, Ness, Lewis. June 2025. (Photo by Mary Stratman)

📷 Angus Murray singing at a public talk, Comunn Eachdraidh Nis, Ness, Lewis. June 2025. (Photo by Mary Stratman) 📷 Marybelle MacKinnon, Crossbost, Lewis. March 2022. (Photo by Frances Wilkins)

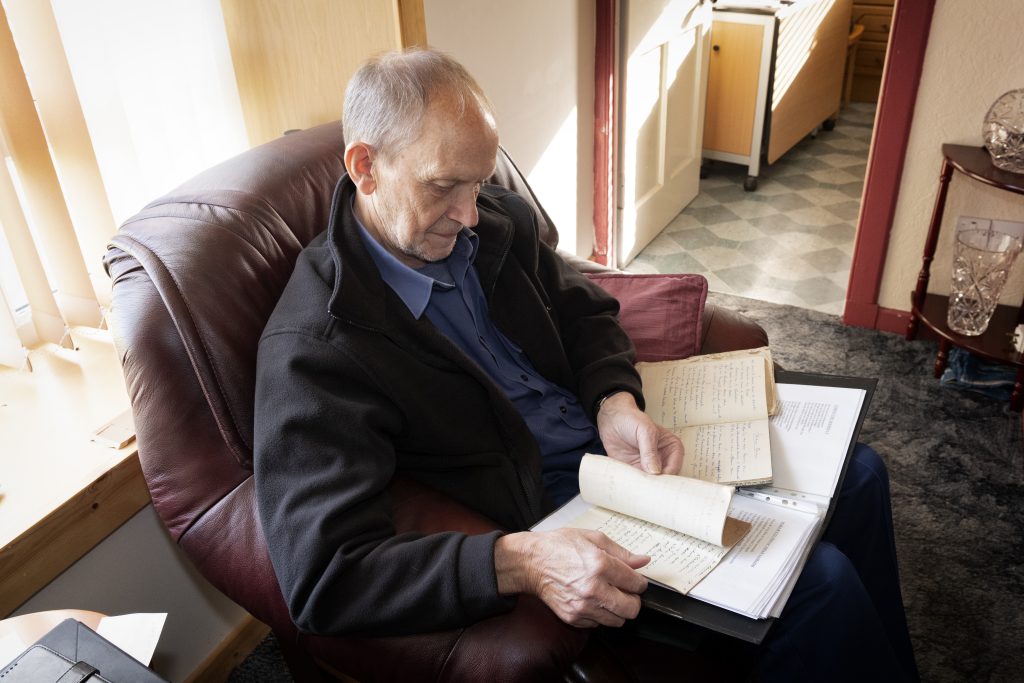

📷 Marybelle MacKinnon, Crossbost, Lewis. March 2022. (Photo by Frances Wilkins) 📷 Murdo J Morrison, bard and Gaelic psalm precentor, Fivepenny, Ness, Lewis, March 2022. (Photo by Mairi M Martin)

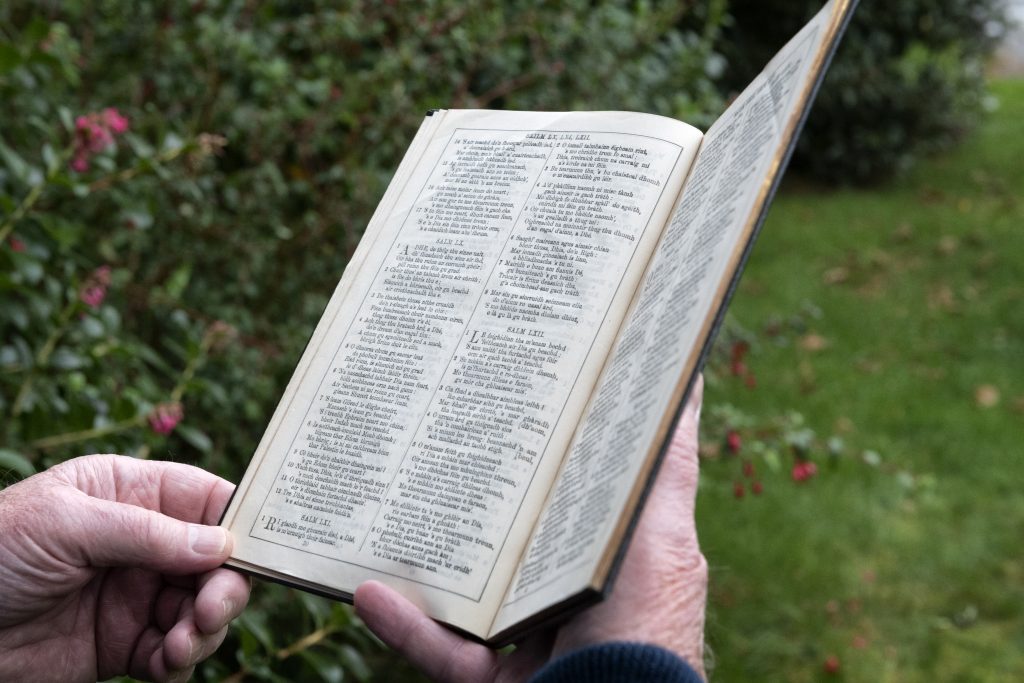

📷 Murdo J Morrison, bard and Gaelic psalm precentor, Fivepenny, Ness, Lewis, March 2022. (Photo by Mairi M Martin) 📷 Gaelic psalter. (Photo by Mairi M Martin)

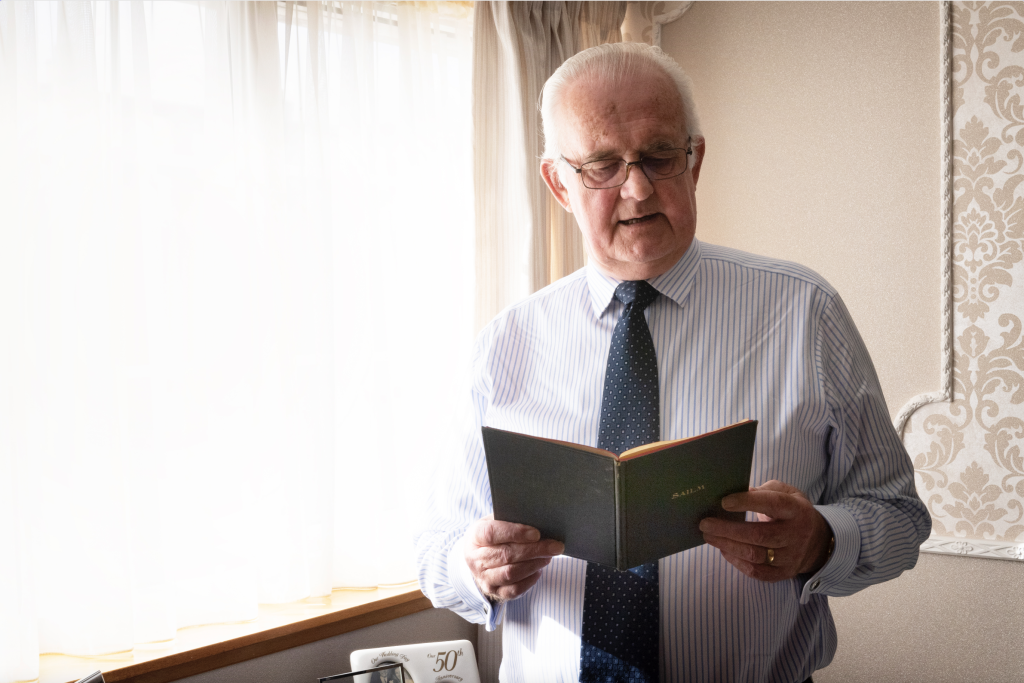

📷 Gaelic psalter. (Photo by Mairi M Martin) 📷 D R MacDonald, Gaelic psalm precentor, Stornoway. October 2022. (Photo by Mairi M Martin)

📷 D R MacDonald, Gaelic psalm precentor, Stornoway. October 2022. (Photo by Mairi M Martin) 📷 Children from Sgoil nan Loch who sang a Gaelic psalm at the Stornoway Mòd, winning first place. With Gemma Malcolm, Kinloch Historical Society. June 2025. (Photo by Mary Stratman)

📷 Children from Sgoil nan Loch who sang a Gaelic psalm at the Stornoway Mòd, winning first place. With Gemma Malcolm, Kinloch Historical Society. June 2025. (Photo by Mary Stratman) 📷 Frances Wilkins with Hamish Taylor, Leverburgh, Harris. June 2025. (Photo by Mary Stratman)

📷 Frances Wilkins with Hamish Taylor, Leverburgh, Harris. June 2025. (Photo by Mary Stratman) 📷 Jeanna Cumming singing at public talk, Leverburgh, Harris. June 2025. (Photo by Mary Stratman)

📷 Jeanna Cumming singing at public talk, Leverburgh, Harris. June 2025. (Photo by Mary Stratman) 📷 Frances Wilkins and Kristine Kennedy at the British Academy, London. May 2025. (Photo by Oliver Wilkins)

📷 Frances Wilkins and Kristine Kennedy at the British Academy, London. May 2025. (Photo by Oliver Wilkins)

Photo taken at Gran’s House Studio, September 2024 (left to right: Dan Brown, Sam Mabbett, Callum Convoy, Chris Waite)

Photo taken at Gran’s House Studio, September 2024 (left to right: Dan Brown, Sam Mabbett, Callum Convoy, Chris Waite)

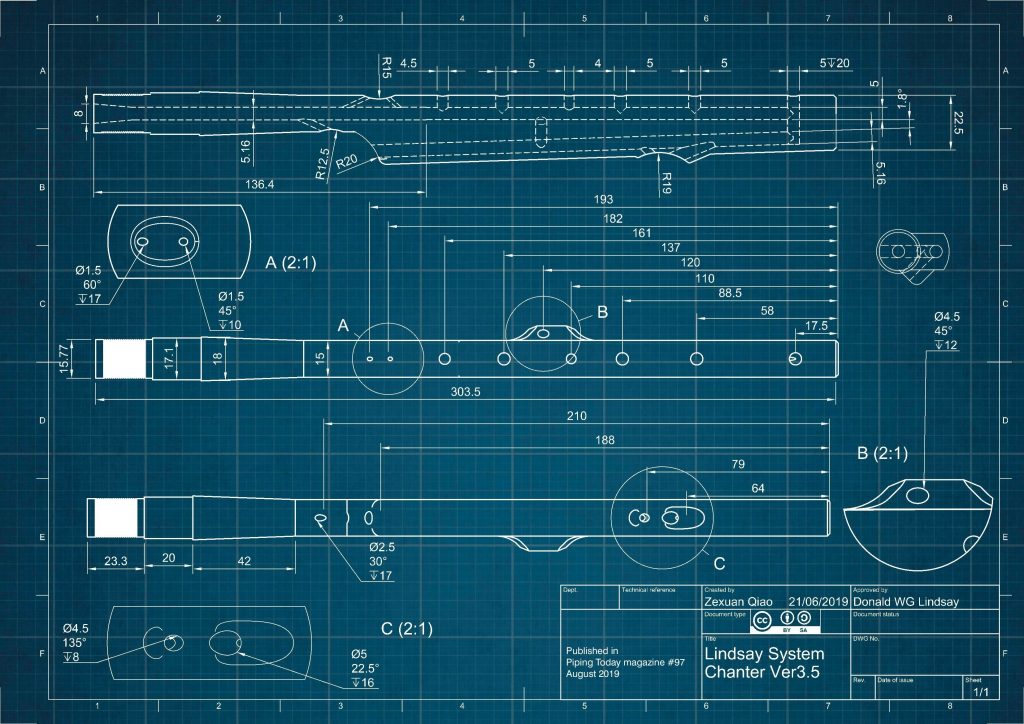

Blueprint: Draft drawing by Zexuan Qiao, based on models and data provided by Donald Lindsay. Originally typeset, colour graded, and published in Piping Today (issue 97).

Blueprint: Draft drawing by Zexuan Qiao, based on models and data provided by Donald Lindsay. Originally typeset, colour graded, and published in Piping Today (issue 97).